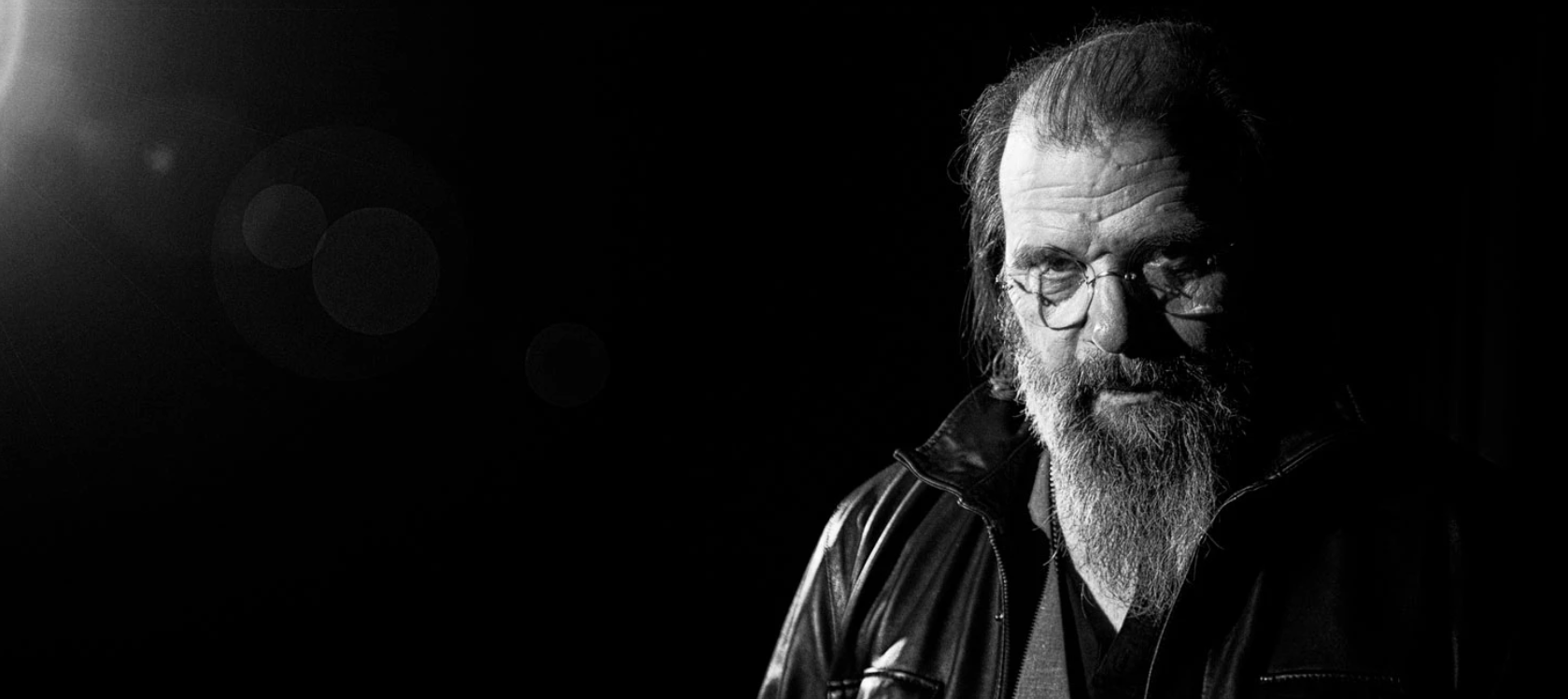

Steve Earle, a man who doesn’t mind telling a story, was talking about the first thing Guy Clark ever said to him.

“It was 1974, I was 19 and I had just hitch-hiked from San Antonio to Nashville,” Earle said in mid-Texas-cum-Greenwich Village drawl. “Back then if you wanted to be where the best songwriters were, you had to go to Nashville. There were a couple of places where you could get on stage, play your songs. They let you have two drafts, or pass the hat, but you couldn’t do both.

“If you were from Texas, and serious, Guy Clark was a king. Everyone knew his songs, ‘Desperados Waiting For A Train,’ ‘LA Freeway,’ he’d been singing them before they came out on Old No. 1 in 1975.”

“So I was pretty excited when I went into the club and the bartender, a friend of mine says, ‘Guy’s here.’ I wanted him to hear me play. I was doing some of my earliest songs, ‘Ben McCullough’ and ‘The Mercenary Song.’ But he was in the pool room and when I go in there the first thing he says to me is ‘I like your hat.'”

While it was a pretty cool hat, Earle remembers, “worn in just right with some beads I fixed up around it,” Clark did eventually hear his songs. A few months later he was playing bass in Guy’s band.

“Now, I am a terrible bass player…but I was the kid, and that was what the kid did. I took over for Rodney Crowell. At that time Gordon Lightfoot’s ‘Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’ was a top ten hit, which was amazing, a six and half minute story song on the radio. So Guy said, ‘we’re story song writers, why not us?’ So we went out to cash in on the big wave.”

The success of ‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’ was not replicated, but Earle reports that being the 19-year-old bass player in Guy Clark’s band was “a gas.” At least until Earle went into a bar and left the bass in the back seat of his VW bug, from which it was promptly stolen. “It was a nice Fender Precision bass that belonged to Guy, the kind of thing that would be worth ten grand now. He wasn’t so happy about that.”

More than forty years later, Steve Earle, just turned 64, no longer wears a cowboy hat. “It was more than all the hat acts,” Steve contended. “My grandmother told me it was impolite to wear a hat indoors.” As for Guy Clark, he’s dead, passed away in 2016 after a decade long stare-down with lymphoma. But Earle wasn’t ready to stop thinking about his friend and mentor.

“No way I could get out of doing this record,” Steve said when we talked over the phone from Charlotte, North Carolina, that night’s stop on Earle’s ever peripatetic road dog itinerary. “When I get to the other side, I didn’t want to run into Guy having made the TOWNES record and not one about him.”

Townes van Zandt (subject of Earle’s 2009 Townes) and Guy Clark were “like Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg to me,” Steve said. The mercurial Van Zandt (1944-1997) who once ordered his teenage disciple to chain him to a tree in hopes that it would keep him from drinking, was the On The Road quicksilver of youth. Clark, 33 at the time Earle met him, was a longer lasting, more mellow burn.

“When it comes to mentors, I’m glad I had both,” Earle said. “If you asked Townes what’s it all about, he’d hand you a copy of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. If you asked Guy the same question, he’d take out a piece of paper and teach you how to diagram a song, what goes where. Townes was one of the all-time great writers, but he only finished three songs during the last fifteen years of his life. Guy had cancer and wrote songs until the day he died…He painted, he built instruments, he owned a guitar shop in the Bay Area where the young Bobby Weir hung out. He was older and wiser. You hung around with him and knew why they call what artists do disciplines. Because he was disciplined.”

“GUY wasn’t really a hard record to make,” Earle said. “We did it fast, five or six days with almost no overdubbing. I wanted it to sound live…When you’ve got a catalog like Guy’s and you’re only doing sixteen tracks, you know each one is going to be strong.”